Tag: nutrition

-

10 super healthy switches to boost nutrition

Here’s some simple easy changes to boost your nutrition. Check my website for recipes and to sign up to my newsletter.

-

Staying alive in toxic times

Photo by Demure Storyteller on Unsplash

-

Facts of rice

A lot of my clients rely on white rice or pasta for quick meals. I thought I would write this blog about the benefits of brown rice and how to prepare it. Hoping to convince you all that brown rice is the way forward. Brown rice is a whole grain and a major source of…

-

What’s in season?

-

How to Optimise Your Vitamin D Level

There are two major forms of vitamin D from two different sources. In the UK our main dietary sources of vitamin D are food of animal origin, foods fortified with vitamin D and supplementation. Naturally rich food sources include egg yolk and oily fish such as salmon, mackerel, herring and sardines. Absorption We probably absorb…

-

All about the menopause

Bullet point summary Peri menopause – the window of opportunity Lots of women dread the menopause. It’s often viewed as a process of ageing and associated with uncomfortable symptoms ranging from heavy periods to weight gain, anxiety and night sweats. Lara Biden, author of the ‘hormone repair manual’, reframes this as a “window of opportunity”…

-

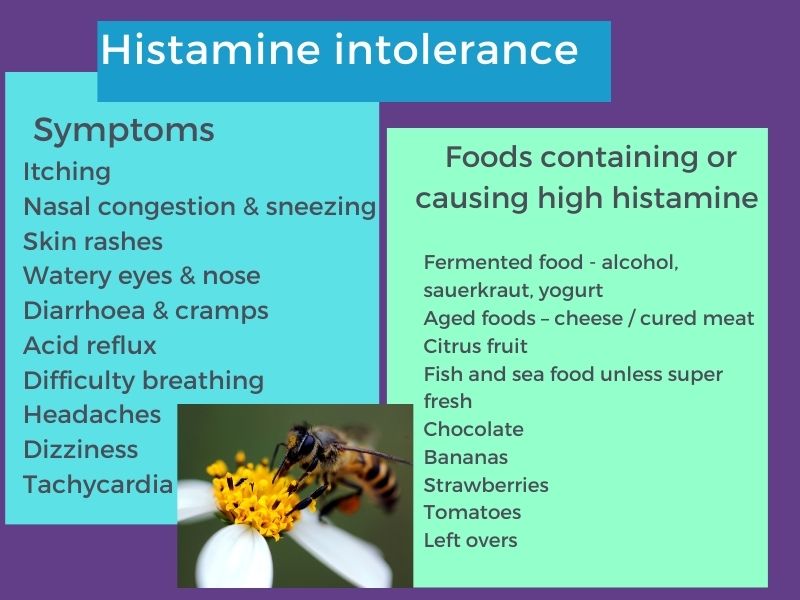

Histamine and histamine intolerance.

Histamine Histamine is an important immune molecule which certain foods trigger the immune system to release. As part of our immune response to bacteria, viruses or other pathogenic microorganisms it increases vascular permeability. This allows white blood cells and proteins access to pathogens through mechanisms such as runny eyes or nose, sneezing, coughing and itching,…