Having surgery? Here are your nutrition guidelines.

I frequently support clients who have either had or are going to have surgery of various kinds.

It is common knowledge that your nutritional status and health prior to an operation has a big impact on the outcome of surgery and your recovery post operation. It is estimated that between 24% and 65% of patients are malnourished and unfortunately this tends to increase during hospital stays. Nutritional supplementation has been shown to reduce hospitalisation costs being associated with fewer complications and shorter stays.

The biggest issues are muscle loss due to tissue breakdown and metabolic demand exceeding supply due to the increase in stress and energetic demand. Micronutrient status is also important but will be covered in a separate blog. This article is focused on protein and carbohydrate requirements both pre and post operation.

There some easy strategies you can implement to help with muscle preservation and to support and accelerate healing. Carbohydrate consumption pre-operation helps to:

- Support increased energy demand during the initial period and to cope with the initial inflammatory state.

- Reduce muscle wastage and preserve lean body mass.

- Manage the insulin resistance which is common post-surgery. Remember insulin resistance will prevent glucose entering your cells. This is important because the body will generate its own glucose (gluconeogenesis) due to the stress and it is important that the cells can absorb this.

Post-surgical amino acid supplementation has been shown to effectively reduce the turnover of whole-body protein and muscle breakdown, and to stimulate an increase in protein generation.

General guidelines for nutrition before and after

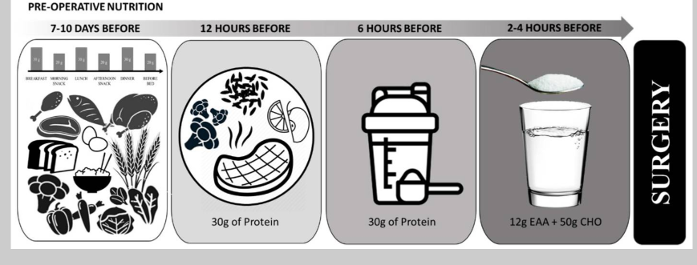

Pre-Operative Nutrition

The goal is to prepare the body for the stress of surgery, support increased metabolic demand, whilst offsetting the consequences of the breakdown of body protein. The goal of pre-operative nutrition is to ensure adequate energy stores to meet the demands of the stress state. The goal of post-operative nutrition, on the other hand, is to promote nitrogen balance, reduce the loss of lean muscle mass, and facilitate rapid healing and recovery. The guidelines given here are aimed at minimising some of the metabolic consequences of surgery, using nutritional supplementation to overcome some of the issues that whole foods would otherwise present.

7-10 days prior to surgery - emphasise high-quality carbohydrate and protein intake to ensure optimal nourishment. To maximise glycogen stores, the sports nutrition model suggests consuming ~60% of total energy (8 g per kg body mass) per day of carbohydrate for a minimum of 3–4 days. Protein intakes of 1.2–2.0 g/kg/day, from high-quality protein sources distributed throughout the day (20–40 g of protein per meal) is recommended to help ensure protein needs are met.

6-12 hours before surgery – consume a well-rounded meal emphasising complex carbohydrates and high-quality protein.

6 hours before - begin abstaining from whole foods, but continue to consume protein and carbohydrate containing beverages, such as a protein shake, a sports drink, or chocolate milk. Since modified carbohydrate supplements rapidly empty from the stomach, consumption may sustain glucose levels for the duration of surgery.

2-4 hours before – It is suggested to ingest free form essential amino acids (EAA’s) to promote a positive protein balance. EAA’s contain all nine essential amino acids and do not require digestion.

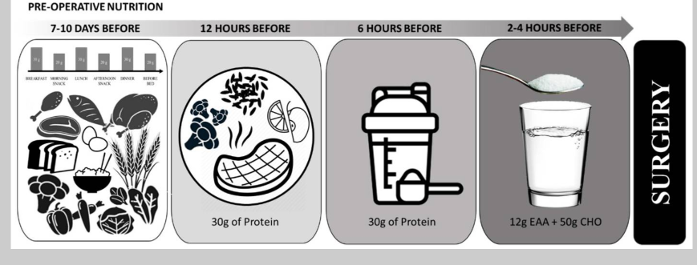

Post-Operative Nutrition

The post operative nutrition model is basically the reverse of the preoperative model.

In the early post-surgery period, patient appetite is often suppressed making consumption of solid foods difficult. During this time, free form EAA’s may help to support the immune system. Patients can transition to protein shakes and sports drinks until they are able to consume whole food sources or meals.

During the rehabilitation period, protein intakes of at least 1.6 g/kg/day and up to 2.0–3.0 g/kg/day is generally recommended. If appetite is reduced and this goal is difficult to meet then consumption of EAA’s and/or protein shakes between meals can help to optimise protein and nutrient intake.

Conclusion

In conclusion carbohydrate intake supports the increased post-surgical energy demand and wound healing. Protein intake supplies the amino acids needed for wound healing, immune function and preservation of muscle mass. Combined amino acid and glucose intake can help to mitigate muscle loss and strength, especially prior to surgery. Following surgery, free form amino acids plus supplementary dietary protein can help to support protein generation and an increase in whole-body protein. Depending on the proximity to surgery different sources of carbohydrate and protein can be used to maximise nutritional intake. Supplemental sources can be useful to support intake during periods when whole foods are not tolerated.

This blog is written to help inform about nutritional needs both pre and post-surgery and is based on scientific rationale. However much of this research is relatively new and further research and trials are needed to elaborate. Therefore this information does not override any medical guidelines given directly to prepare for planned surgery. These will supersede this information unless your medical team are happy to sanction otherwise.

References

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8156786/figure/nutrients-13-01675-f003