Nutritional support for post-surgery

I frequently support clients who have either had or are going to have operations.

It is common knowledge that your nutritional status and health prior to an operation has a big impact on the outcome of surgery and your recovery post operation. It is estimated that between 24% and 65% of patients are malnourished and unfortunately this tends to increase during hospital stays. Nutritional supplementation has been shown to reduce hospitalisation costs being associated with fewer complications and shorter stays.

I have recently been researching this area for a client with impending surgery This blog is focused on protein and carbohydrate requirements post operation. I will consider micronutrient status in a future blog.

Some degree of muscle loss post-surgery is inevitable. Skeletal muscle serves as the primary source of essential amino acids. If protein intake is below the requirement to sustain daily functions the body will breakdown muscle for protein. To compound this the hormonal stress response following surgery can prevent normal protein generation. All of this is often complicated further by the forced rest and immobility due to the surgery itself.

It is important to try to minimise the muscle loss and if exercise is not feasible nutritional strategies can help to mitigate this. In healthy individuals, loss of muscle tissue begins to occur in as little as 48 h of inactivity, with significant loss within five days. This is followed by loss of strength and functionality.

Post-surgical amino acid supplementation has been shown to effectively reduce the turnover of whole-body protein and muscle breakdown, and to stimulate an increase in protein generation.

General guidelines for nutrition post surgery

The goal of post-operative nutrition, on the other hand, is to promote nitrogen balance, reduce the loss of lean muscle mass, and facilitate rapid healing and recovery. The guidelines given here are aimed at minimising some of the metabolic consequences of surgery, using nutritional supplementation to overcome some of the issues that whole foods would otherwise present.

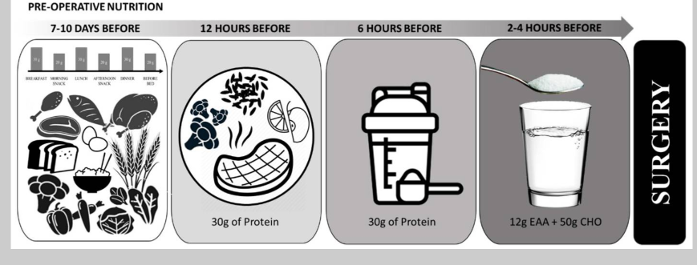

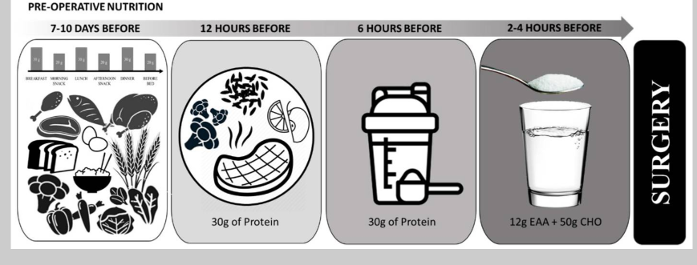

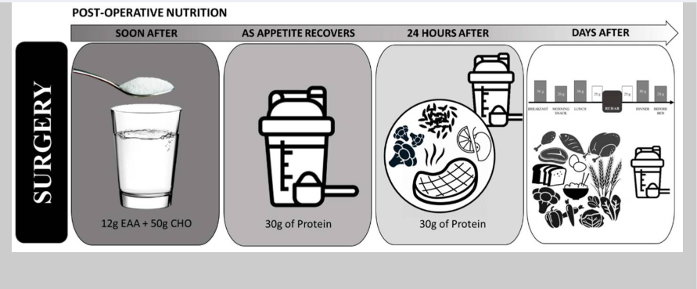

The post operative nutrition model is basically the reverse of the preoperative model.

In the early post-surgery period, patient appetite is often suppressed making consumption of solid foods difficult. During this time, free form EAA’s may help to support the immune system. Patients can transition to protein shakes and sports drinks until they are able to consume whole food sources or meals.

During the rehabilitation period, protein intakes of at least 1.6 g/kg/day and up to 2.0–3.0 g/kg/day is generally recommended. If appetite is reduced and this goal is difficult to meet then consumption of EAA’s and/or protein shakes between meals can help to optimise protein and nutrient intake.

Conclusion

In conclusion protein intake supplies the amino acids needed for wound healing, immune function and preservation of muscle mass. Following surgery, free form amino acids plus supplementary dietary protein can help to support protein generation and an increase in whole-body protein. Depending on proximity to surgery different sources of protein can be used to maximise nutritional intake. Supplemental sources can be useful to support intake during periods when whole foods are not tolerated.

This blog is written to help inform about nutritional needs post-surgery and is based on scientific rationale. However much of this research is relatively new and further research and trials are needed to elaborate. Therefore this information does not override any medical guidelines given directly to prepare for or recover from planned surgery. These will supersede this information unless your medical team are happy to sanction otherwise.

References

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8156786/figure/nutrients-13-01675-f003