Bullet point summary

- Menopause can be reframed as an opportunity for a health drive, a new stage in life experienced by generations of women classified by the Japanese as the “renewal’ years or a return to the freedom and zest of the girl inside.

- There are many physiological reasons for symptoms but they are temporary. It’s a transition phase and there are many options to explore both natural and medical – don’t suffer in silence.

- Your brain and your immune systems both recalibrate. You have to do more with less. This can create some issues but with the right interpretation there are many options that can support the body with these challenges.

- It is harder to stay slim post menopause. There can be up to a 15% drop in metabolic rate from the combined effects of muscle loss, androgen excess and insulin resistance.

- If insulin resistance is present it will amplify peri menopausal and menopausal symptoms. The good news is that diet and lifestyle are super effective at resolving this.

- Chronic inflammation will aggravate menopause symptoms and must be rectified to avoid longer term health issues such as autoimmune conditions.

- Metabolic flexibility underpins a smooth physiological transition. Exercise, intermittent fasting and a healthy gut are key to achieving this.

- A well functioning digestive system and healthy liver function play a significant role in navigating the menopause.

- The adrenal glands are also important for both their stress hormone and oestrogen producing functions. If possible ovaries should be retained.

- Finally a healthy circadian rhythm together with soothing the nervous system and vagus nerve stimulation complete the package of support required.

Peri menopause – the window of opportunity

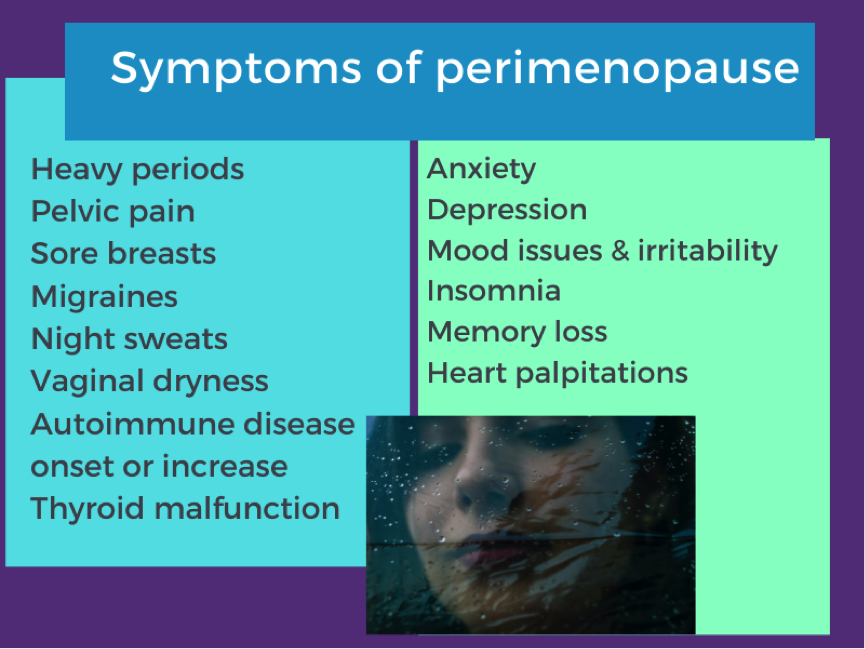

Lots of women dread the menopause. It’s often viewed as a process of ageing and associated with uncomfortable symptoms ranging from heavy periods to weight gain, anxiety and night sweats. Lara Biden, author of the ‘hormone repair manual’, reframes this as a “window of opportunity” to resolve issues which left unaddressed might become problematic later in life.

This blog aims to explain what’s going on physiologically and why. The key things to know are:

- It’s temporary

- It’s a transition phase

- It’s a window of opportunity for health

- There are many options to explore for help with this transition

What is perimenopause?

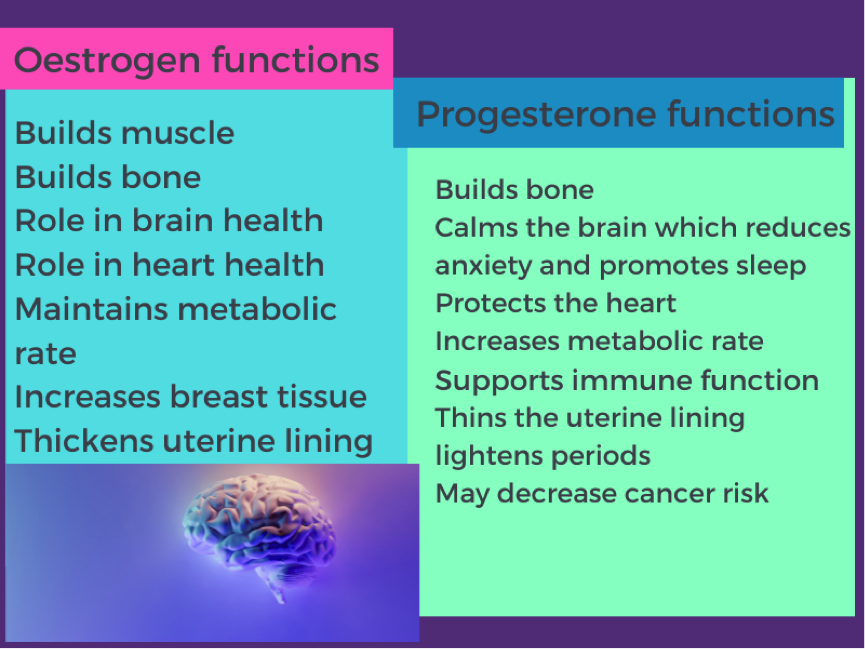

Perimenopause begins 2-12 years before periods stop so the late 30’s to early 40’s. Hormonally the picture resembles a second puberty as the transition is made to a high oestrogen/low progesterone scenario. The only difference is the decline and loss of progesterone whereas in puberty progesterone is gained. Finally oestrogen will return to childhood levels which is just right for this new phase of life.

Symptoms are largely caused by oestrogen as it fluctuates erratically before settling to a new but lower normal. Progesterone also drops which means that the formally stable oestrogen to progesterone ratio is now much higher than in ovulatory years. . Eventually we lose almost all progesterone but we continue to make some oestrogen. This scenario of high but wildly fluctuating oestrogen and low or no progesterone can trigger or exacerbate a number of health symptoms. It also places extra demands on important physiological systems such as our immune system and how we make energy and detoxify the body. During this transition period the body has to learn, or remember, a new way of operation.

Strong symptoms

Strong symptoms are usually due to a combination of genetics, general health status and the condition of your menstrual cycle prior to peri-menopause. If you have a history of menstrual mood symptoms you may be hypersensitive to hormonal variation.

Opportunity for health

Even if you don’t experience symptoms it’s still a time to take extra care of your health as it’s a period of physiological flux. The brain and the nervous system have to work differently. They have to work without oestrogen and progesterone. The brain recalibrates and the immune system remodels. This increases the risk for anxiety, depression and memory loss. Together with sleep disturbance this can lead to chronic pain if no action is taken. All of this is associated with increased vulnerability to heart disease and insulin resistance. There is often a slight temporary cognitive decline and there is a slightly increased risk of mental health issues.

Physiology of perimenopause

Once menopause occurs women have to revert to intracrinology having previously relied on ovarian oestrogen production. This is a process of localised oestrogen production which takes place in tissues such as the heart and brain. This will produce oestrogen at about 10% of previous levels via the enzyme aromatase. Aromatase converts androgen hormones to oestrogen. So oestrogen production continues via increasing androgen production for conversion to oestrogen and up regulating aromatase activity. Androgen hormones include androstenedione from the ovaries and DHEA from the adrenal glands. Hence healthy adrenal glands are essential for a healthy menopause and ovaries should be retained if possible.

Once menopause occurs women revert to a process of localised oestrogen production in tissues such as the heart and brain. An enzyme called aromatase converts androgen hormones to produce about 10% of previous levels of oestrogen. Androgen hormones are produced by the ovaries and from the adrenal glands. Hence healthy adrenal glands are essential for a smooth menopause transition and ovaries should be retained if possible. This process of change may take from months to years hence the variation in symptom length.

Abdominal weight gain

This is a common complaint and has a number of contributing factors. Metabolism slows down without oestrogen and progesterone to stimulate it. Oestrogen helps the body to build muscle so lower levels are associated with less muscle mass and this also slows metabolism.

When oestrogen levels decline this can trigger insulin resistance. This refers to chronically elevated levels of insulin in the blood. Insulin is the hormone that causes cells to accept glucose. If glucose cannot get into cells it will be stored as fat. Insulin resistance is therefore a key factor in abdominal weight gain.

There is a natural shift to androgen excess during this period which perpetuates a cycle of insulin resistance and weight gain. There can be up to a 15% drop in metabolic rate from the combined effects of muscle loss, androgen excess and insulin resistance.

If insulin resistance is present or develops this can lead to over production of an oestrogen called oestrone. This is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, fibroids, pelvic pain, abnormal uterine bleeding and breast cancer. So eliminating insulin resistance is critical for a healthy menopause.

Neurological symptoms: anxiety, depression, memory loss, mood, insomnia and migraines

Your brain is the source of most menopause symptoms because it has to learn to work in a different way. It’s a neurological transition as well as a reproductive one. Following menopause there can be a drop in the brain’s activity and energy levels of up to 25%. Up to now the brain has utilised glucose as its primary source of energy and oestrogen has helped brain cells with this. Now the brain has to shift to using ketones so it utilises fat rather than glucose as its primary fuel source.

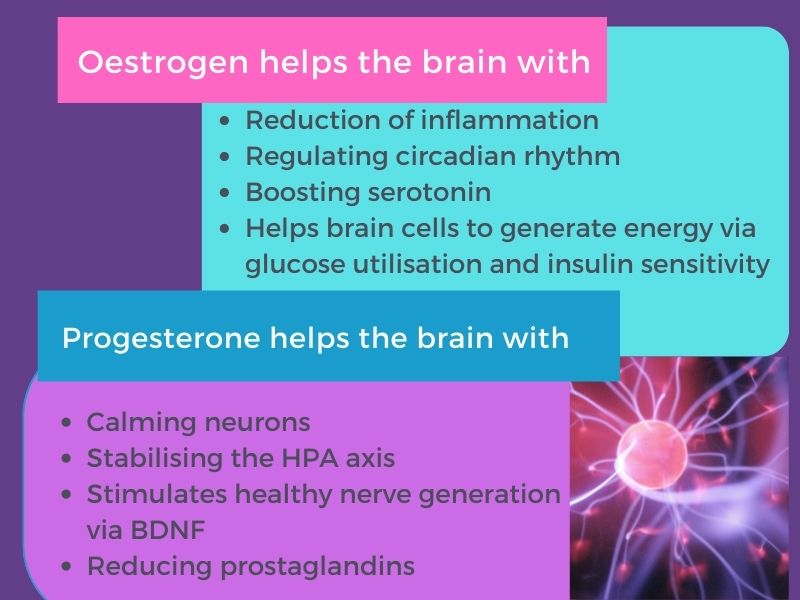

Progesterone and oestrogen both play numerous roles in brain function.

Little wonder then that the brain needs some time to adjust to its new status and that difficulties sometimes arise during this adjustment period. The loss of progesterone can reduce the ability to cope with stress as well as increase the risk of anxiety, depression, memory loss, mood symptoms and sleep disturbance.

Metabolic flexibility is key to help with this adjustment. The body has the enzyme pathway to burn ketones but it’s often switched off from lack of use. This stems from the provision of regular food (glucose) and frequent snacking. The cornerstones to reinstate this pathway are exercise, intermittent fasting, stable blood sugar and a healthy gut with a diverse microbiome.

During menopause the thermoregulatory mechanism in the brain narrows and there is far less tolerance to temperature changes. Researchers believe hot flashes are caused by the temperature sensor in the brain called the hypothalamus. Falling oestrogen levels and lower amounts of serotonin and adrenaline all affect the hypothalamus. This means that in the task of managing menopause symptoms the importance of stress management cannot be overstated.

The final symptom the brain may trigger is migraines. This is attributed to oestrogen fluctuations and the loss of progesterone’s calming influence. Iron deficiency from heavy periods can also be a factor here.

The immune system

The immune system also has to recalibrate during perimenopause. Progesterone calms the immune system and during the reproductive years your body is used to regular doses of oestrogen and progesterone. Losing the anti-inflammatory properties of both hormones can cause problems with the immune system including chronic inflammation or triggering autoimmune issues such as autoimmune thyroid disease. Any inflammation has to be addressed as it will make menopause symptoms worse and increase insulin resistance.

It is also essential to sort out any issues with digestion and liver detoxification as both of these can contribute to sources of inflammation. Most of your immune system is located around your gut and it constantly communicates with your gut bacteria. If anything goes wrong this activates your immune system causing inflammation. Your liver is responsible for deactivating oestrogen which is then removed from the body via the bowel. If your gut bacteria aren’t healthy you can get something called ‘gut-liver-recirculation’ where oestrogen gets reactivated and reabsorbed in a more toxic form.

Autoimmune thyroid disease

The loss of progesterone can be a trigger for autoimmune thyroid problems as it reduces the availability of thyroid hormone. There is a lot of overlap between symptoms of perimenopause and thyroid issues so this can easily be missed. In addition both of these conditions overlap with symptoms of insulin resistance because of the interplay between the hormones involved. Thyroid disease is more common in women and increases over the age of 40 with a one in ten chance of incidence. This is a complicated area and practitioner help is recommended.

Heavy or painful periods and breast pain

During perimenopause oestrogen can spike up to three times its normal level and fluctuates erratically. Oestrogen thickens the uterine lining and without progesterone to counteract this the menstrual flow can increase along with pain. For both heavy periods and severe pain it is essential to see your doctor for an assessment. The most common cause is anovulatory cycles where oestrogen is made but not progesterone. However there are other possibilities that need to be ruled out the main ones being endometriosis; adenomyosis; fifibroids; anovulatory bleeds; thyroid disease; bleed disorders. Heavy periods can also result in iron deficiency which manifests in fatigue, breathlessness, hair loss and easy bruising.

Period pain such as cramping which is inconvenient but less severe is usually caused by prostaglandins. These hormone type compounds constrict blood vessels which contributes to period pain. They can be triggered by high levels of oestrogen as it fluctuates during perimenopause. The latter can stimulate high histamine and mast cell activation both of which can cause prostaglandin release. Before perimenopause this activity was often regulated by progesterone. It might be worth trying a dairy free diet as this may reduce prostaglandins, histamine levels and mast cell activation. Fortunately diet and lifestyle and key micronutrient supplementation can often resolve this.

Breast soreness or tenderness can be caused by high oestrogen levels but can also be a sign of iodine deficiency. Addressing the core strategies already highlighted will generally resolve this.

How to navigate the menopause

- Nutrition including micronutrients

- Exercise

- Sleep and stress management

- Tackle any current health issues such as insulin resistance, poor digestion, thyroid issues, poor oestrogen detoxification and chronic inflammation.

- Medication – HRT

I can help you

- To identify where you are in the stages of perimenopause/menopause and what you need to consider to support your health.

- To assess if you have insulin resistance and how to reverse this if it’s caught early enough. This is key for abdominal weight loss.

- The importance of exercise for insulin resistance and which type is best.

- How to use nutrition to maximise hormone balance and stabilise your levels of oestrogen and androgen production.

- How to include phytoestrogens in your diet – what they are and how they can help.

- How to stabilise your blood sugar levels.

- How to cultivate metabolic flexibility and undertake intermittent fasting and why this might be helpful.

- Understand why dairy can be an issue.

- The pro’s and con’s of HRT and which is right for your individual situation.

- Why your liver function is so important and how to revitalise it.

- How to breathe to stimulate your vagus nerve and also improve your parasympathetic nervous system and heart rate variability to build resilience.

- Check your micronutrient levels in case you need to temporarily supplement to optimise these especially in relation to cognition and sleep.

- The importance of a healthy thyroid gland and sufficient thyroid hormone and if there is a thyroid issue why it is critical to know if your condition is autoimmune.

- The importance of healthy adrenal glands and how to support these.

References

Briden, L. (2021) The hormone repair manual. Greenpeak Publishing

Dong, T. A. (2020) Intermittent Fasting: A heart healthy dietary pattern; The American Journal of Medicine:133(8):pp.901-907 DOI: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.03.030

Labrie, F. ( 2017) Science of intracrinology in postmenopausal women; Menopause: 24(6); pp.702-712; doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000808.

Mosconi, L. (2021) Menopause impacts human brain structure, connectivity, energy metabolism, and amyloid-beta deposition; Nature:11:10867; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90084-y

Wilcox, G. (2005) Insulin and insulin resistance; The Clinical Biochemist reviews; 26(2):pp.19-39

Leave a Reply